In scientist-turned-film-maker Randy Olson’s new book, Don’t Be Such a Scientist: Talking substance in an age of style, he argues that scientists ought to take a few notes from Hollywood when trying to communicate ideas to the general public.

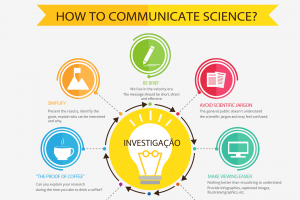

Whether you are trying to persuade people of the dangers of climate change, the reality of evolution or the mystery of dark energy, here are a few of Olson’s tips for scientists who want to get their message across.

Take an improv class

Scientists are instilled with a dreaded fear of wrongness. To say something wrong as a scientist is to not be a scientist at all.

The fear is justified at scientific meetings, but when you’re talking to the general public, it’s a different arena. You’re at the introductory level of knowledge. Relax. Trust yourself. Your audience can sense the fear, and they don’t like it.

There’s a way for scientists to deal with this. It’s called improv acting. Improv teaches you to relax, be “in the moment”, to “get out of your head”, to be more spontaneous – all things that the general public responds to.

Scientific training by itself won’t lead you in this direction. Sometimes you have to take extra efforts to offset what science does to your mind and your persona.

Improv training is usually geared towards comedy, but the basic rules and techniques apply to life in general. One of the best traits it teaches is how to listen. This is something scientists often have difficulty with.

As a scientist you are trained to know your field, then be authoritative and give lectures. While lip service is paid to the idea of listening to feedback and interacting, the truth is that the intensity of scientific research can lead to a tendency to want to plan and control everything (isn’t that what controlled experiments are all about?).

That’s fine in the laboratory, but when it comes to speaking to the public, an overly controlling tendency can be off-putting. Improv leads you in the opposite direction.

Look into an introductory class. If nothing else, it will be a huge amount of fun.

Invest in marketing

“Honesty good. Marketing bad.” Those are admirable words to live by in general. But marketing is just a subset of a larger topic: communication.

Once you have a good, solid piece of information, you need to accept that in today’s information-glutted world, facts by themselves usually aren’t enough to capture the attention and interest of the public. You have to wrap those facts up in a package (a process that you could theoretically call marketing) and “sell” it to your audience.

In the book I mention that the independent film Napoleon Dynamite was produced for only a few hundred thousand dollars, but the distribution company that bought it, knowing it had a winner on its hands, gambled $10 million in advertising. So it ended up spending over 90 per cent of its budget on promoting its product. It was a winning strategy, and the movie earned over $50 million.

In contrast, the heavily science-influenced Pew Oceans Commission released its final report in 2003, spending only 3 per cent of its budget on promoting its product. Is it any wonder that it failed to have much effect?

Yet this is what scientists tend to do: they tend to believe in the power of information alone to sell itself. I hate to be too cynical, but you have to be realistic. In today’s world of noise, information is too easily drowned out.

To illustrate what I’m saying, I’m currently up to my neck in the issue of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) on the California coast. We’ve pinpointed a single scientific fact that the public needs to know: MPAs work.

Protecting parts of the oceans helps marine life recover from over-exploitation. Scientists weren’t certain of this a decade ago, and there are still limitations, but the science community is now willing to make the simple utterance: MPAs work.

Knowing that fact isn’t enough. We need other people to know. So now I’m “marketing” this piece of information with a cool logo on T-shirts, a fun website we’re about to unveil where characters speak to you and a television commercial starring Pierce Brosnan and other celebrities.

We have a good product that we believe in. Now we’re doing the dance of marketing it.

Arouse, then fulfil

I was asked recently what I thought was the most important point of the book. I’d have to say it’s the simple couplet I was told by a communications professor over a decade ago: “Arouse and fulfil.”

First you need to arouse the interest of your audience, then you need to fulfil the expectations that you’ve created. Arouse and fulfil.

Do it in that order. Don’t do it in the reverse. Don’t tell me a ton of information, then tell me something intriguing that suggests why I should care. You will have lost me by then.

Scientists have very little problem with the second part. They know how to fulfil you to the end of time. Just wind most scientists up and let them go. Telling someone how interesting science is comes easy; showing them takes effort.

It’s the difference between a statement and a question. If I ask you to tell me about yourself in three statements you can probably start talking immediately, but I may not find it very engaging.

But if I ask you to say it in the form of questions, they will take some time to craft. The time you spend coming up with good questions will be doing me a favour, because the questions will light a fire in my mind that will make me want to hear more of what you have to say, not less.

Be bilingual

Ever hear someone “talking shop” at a cocktail party? Ever done it yourself? It’s awful, really.

But there’s a way to avoid it: be bilingual. Learn to speak one language at work, and another at the cocktail party.

When it comes to science, there’s an academic language and a general public language. Some of the basic elements of this divide are obvious. You don’t want to talk about “hyperstatic metastable states” at the cocktail party (usually) and you don’t want to tell dirty jokes in your science talk at a meeting.

But other elements are not as intuitive – such as the need to be more visual with the general public.

A certain hoity-toity academic last year opined on the poor craftsmanship of an anti-evolution movie, complaining that the film-makers felt the need to provide a visual image for every word that was mentioned in the narration.

Well, that style might get annoying for academics, who are able to process words and use them to create visual images in their mind. But most of the general public isn’t like that. If you want them to get something, you’d better show them rather than just tell them.

It sounds obvious, but it isn’t. Try going to film school and making a ton of films. You will eventually be forced into the realisation that seeing is believing, so most people simply have to be shown.

Tell a good story

In the end, this is perhaps the most important piece of advice, and it grows out of the “arouse and fulfil” principle.

The world today is so overloaded with information there simply is not enough time to process everything that everyone is saying. How many books do you have that you still want to read but haven’t gotten to? How big is your stack of unwatched DVDs?

And yet, if a friend tells you tomorrow that a certain movie is, “A really great story about…” you’ll probably move it to the top of your list.

Tell a good story and the whole world will listen. And this is a principle that holds for both audiences: academic as well as the general public.

A lot of people respond to this advice with, “Yeah, right, I already know that.” Then why don’t you do it?

Great storytelling is infinitely difficult and elusive. If it were easy, they wouldn’t pay so much money in Hollywood to professional story analysts. It’s not easy, but it’s so powerful it’s worth the effort.

Who’s the life of the party? The guy who tells the great stories. And who’s the most popular speaker at a scientific meeting? Usually the speaker who also tells good stories, even though they are woven out of completely accurate facts.

Storytelling is the unifying trait between the sciences and the humanities. Scientists don’t like to think about this, but it’s true. The world of science has storytelling at its core.

If you don’t believe it, all you have to do is look at a typical research paper: it’s written in the basic three-act structure: act one is the introduction (exposition!); act two is the methods and results (the body of the story, where events actually happen); act three is the discussion (the return of the subjective element for the grand synthesis).

It’s a formula old as the ages, and as important today, in the age of information overload, as ever. A good story is like Jello: there’s always room for it.

Source: New Scientist (Randy Olson)